English

A shoutout to Geoff Lindsey, an English phoneticist who’s been pushing for English phonetic transcription reform. Check out his work on his blog and YouTube.

Phonetic Reform

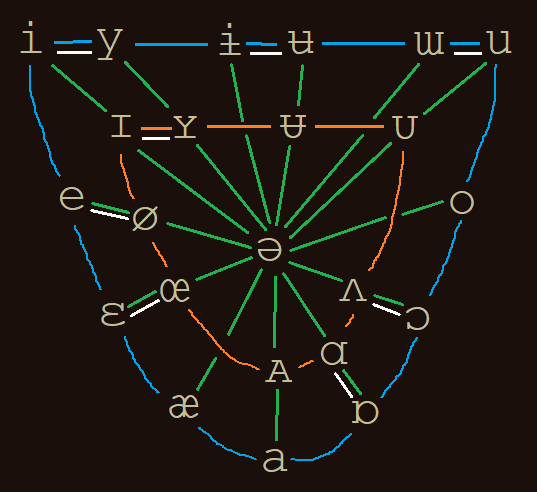

The first step to learning a foreign language for an English-speaking native is to understand the sounds of eir own language. The inaccuracy of the standard symbols is a core reason that English speakers have garbage accents for any foreign language they touch. So let’s push for more accurate vowels: here’s Lindsey’s system, which represents my native accent, called Southern Standard British.

Note that I write the open front unrounded vowel with æ, leaving a for the cardinal (central) open vowel (often denoted ä). I do this because my familiar languages are native English, Serbian, and an array of European languages that use central a. I also visualise the vowel space as a triangle with corners at a/i/u.

This diagram has a few other custom symbols I felt like including, but the only one I use below is ɵ, which is Ʉ in the diagram.

| type | short | e.g. | long (→r) | e.g. | long (→j) | e.g. | long (→w) | e.g. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | æ | pat | ɑː | par | ɑj | by | æw | bow (🙇) |

| e | ɛ | pet | ɛə | pear | ɛj | bay | ||

| i | ɪ | pit | ɪə | peer | ɪj | bee | ||

| o | ɔ | pot | oː | pour | oj | boy | əw | bow (🏹) |

| u | ɵ | put | ɵə | pure | ʉw | boo | ||

| ʌ | ʌ | putt | ||||||

| ə | ə | abbot | əː | purr |

In my accent, the other two distinct vowel groups are the allophones of ʉw and əw before l, namely ʊw (pool) and ɔw (pole).

Other accents have further groups, notably r-free long vowels (ɑː in spa and oː in saw), r-ful short vowels (ɚ in letter), ʌr (e.g. scottish word) and a split between war and wore, as well as words merged to different groups of course, but I stuck to the 22 unique vowel sounds in my accent here.

Features that distinguish most British accents (and some others) in general are:

- the universal use of linking r/j/w sounds, so for example we will pronounce “law and order” as “lorandoːder”, despite the lack of r in the word. Per Lindsey, the linking j/w are interpreted as already being there as part of the standalone vowel sounds in the original words.

- the lack of r-coloured vowels or other pronunciations of r, unless linking.

- as a result, ɛə/ɪə/ɵə are often colloquially (entirely for some people unlike me) reduced to ɛː/ɪː/ɵː.

- the ʌ sound (which in my case sounds very close to a short ɑː, as in spɑ, whereas most Americans pronounce it the same as ə (abbot)).

- actual length distinction between short and long vowels (as labelled above), hence being able to contrast ʌ and ɑː unlike Americans.

The three features that most set apart my accent from northern British accents (let’s take East Midlands as the most vanilla example of a northern accent) are:

- preferring ɑː to æ for many words like ask.

- short ʌ is completely split from short u (so we never rhyme but with put, not even colloquially).

- pronouncing all ending i sounds as ɪj rather than ɪ (Grims-bee vs bih).

My personal accent has a few idiosyncracies that cropped up thanks to learning native English and Serbian simultaneously, like pronouncing London /lɔndən/ instead of /lʌndən/, once (and other words spelt “nc”) as /wʌnts/ instead of /wʌns/, and want as /wʌnt/ rather than /wɔnt/.

Spelling Reform

Intro

English spelling is so bad that it takes children 3× longer to pick it up than a typical first language, and whether or not a language becomes an international lingua franca or remains confined to a few villages, it’s always the move to reform this kind of thing. For me, reform should be a dynamic thing, introducing several co-existing standards and letting the most popular win out. I’ve written my own proposal here, based on the idea of giving a phonetic spelling based on my accent. I think different accents should, where necessary owing to overlaps in lexical sets, be represented with different mutually-intelligible spellings.

It’s interesting how severely English pronunciation varies from generation to generation compared to languages with stable spelling, and the use of accent as a class marker. RP dying out is a good step in the right direction for having class die out, in the society most in need of that perhaps in the world (England), so I think making our spelling more phonetic, more European, and less prescriptive will help with class and international integration, while still allowing our beautiful regional accents to survive.

If you still ain’t convinced, have a hilarious MSN convo between me and my Serbian cousin from when we were 15

So with that, I’ll set out my spelling system.

Alphabet

6 letters added, 4 removed (x is considered a new letter)

Consonants: b, p | f, v | s, z | ſ, ʒ | þ, ð | t, d | k, g | h | l, m, n | r, w, y

Vowels: a | e | i | o | u | ʌ | x

Added: ſ (ʃ), ʒ (ʒ) | þ (θ), ð (ð) | ʌ (ʌ) | x (ə) (IPA values in bold)

Removed: c | j | q | x

The consonants all retain their usual sound values, with 4 new ones for sh, zh (vision), and both kinds of th. The vowels represent the 7 short sounds in the phonetic table above. I picked “x” for ə because it’s a simple glyph serving a very common letter (in an old draft, I was using “ø” instead, so you can use that if you find “x” too abrupt a change).

European Vowels [aside]

In order to not make English look too different, I retained “y” for [j] (so hey is still written “hey” rather than “hej”). In order to serve other European languages tho, I’d prefer this alphabet to use a few more standard vowel sounds, based largely on Ancient Greek orthography. Namely (using French as an example):

- y (y – e.g. pu, thus using j for j)

- ø (ø/œ – e.g. peu)

- ω (ɔ – e.g. motte, as opposed to mot)

- ε (ε – as in è, as opposed to é)

Thus, a base of 10 common vowels across languages would be i, e, ε, a, ω, o, u, y, ø, x – 7 cardinals, 2 rounded front vowels (umlaut ö/ü) and 1 fully mid/reduced vowel.

The vowels of most languages could be matched up to these, tho there’ll sometimes be little distortions in pronunciations where vowels get bunched up. For example, English /ʌ/ could be switched to the glyph “ω” (per my proposal, the phoneme that glyph usually represents, /ɔ/, would be written “o”, and /oː/ would be “oo”). Polish already uses “y” for /ɨ/ and Finnish could use “ε” for /æ/ (instead of “ä”).

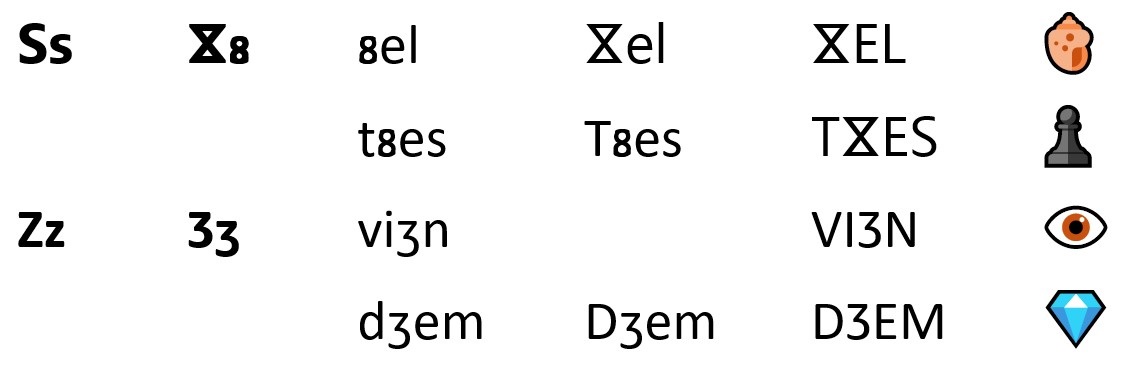

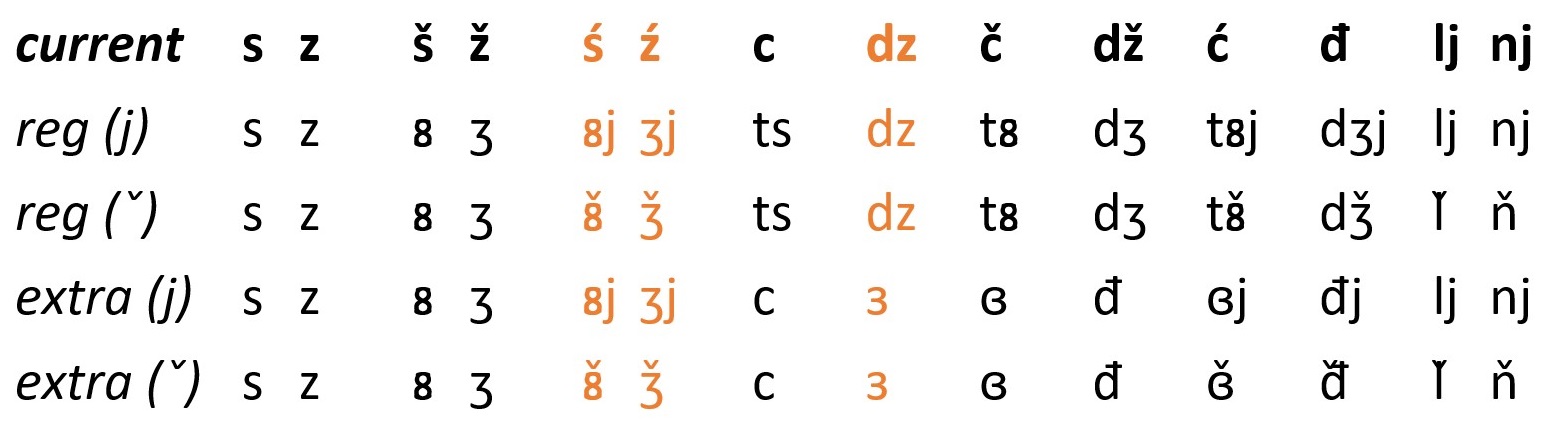

Latin Sh Consonants [aside]

An idea I’ve preferred lately tho for European languages is to keep “x” to its traditional use as /x/ (usually spelt “ch” as in “loch”). Then, since giving /ʃ/ its own letter is high-priority for Latin scripts to help cut down on the number of di/trigraphs and diacritics, it’d make sense to define one as a cross between s and x, for example reflecting the evolution of “sch” from Dutch /sx/ into German /ʃ/.

For Slavic languages, that’d clean things up to, say (where ˇ is used for palatalisation):

Vowels

The system is basically the phonetic table above, with the rows giving the vowel letter and the columns giving a following consonant letter, to make 1-or-2-letter-pairs representing a distinct vowel sound. The only exception is the r-less pure long vowels (spa, saw), which are spelt with a doubled letter (aa/oo, so spaa, soo); these are pronounced the same as ar/or in non-rhotic accents.

Short (-): a, e, i, o, u, ʌ, x

Long (-r): aa/ar, er, ir, oo/or, ur, xr

Long (-y): ay, ey, iy, oy

Long (-w): aw, ow, uw

The use of r/y/w here is not as standalone phonetically-spelt sounds, but rather as indicators for the pronunciation of the preceding vowel (marking it as a long diphthong of a certain type). Notably, most of these “r”s aren’t pronounced as r in my native accent.

The ʊw/ɔw before-l allophones would be spelt the same as their usual forms (so “uw”/”ow”).

Sample

ðx kwik brawn foks dʒʌmpt owvr ðx leyzi dog

may parxgraaf on lʌv

For miy, lʌv iz x raaðr vaykeriyxs fiyling ðat ay sxspekt izn’t riyl, bʌt fir ay mey biy swolowing x bitr pil bay cxnsidring may own ekspiriyxns as biying reprxzentxtiv of evriywʌn els’s. Ay felt bay ðiy end ðat lʌv woz mor of x sxspendid disbxliyf nesxseri tuw fʌnkſxn as x pxrsxn, wʌn ðat may sowſxl skilz wxrn’t ʌp tuw ðx taask of sxspending

Analysis

Variation

This is by no means intended to be a perfectly phonetic orthography. For example, it doesn’t distinguish many free-varying allophones such as /ŋ/ (singer) vs /ŋg/ (finger), and has some simplifications like:

- spelling happy as “hapi” rather than “hapiy”, so preferring the northern English pronunciation to the southern because it’s shorter to spell.

- likewise, “owvr” is preferred to “owvx”, despite syllabic r (r-coloured schwa) not existing in British English, because it cognitively sounds like an r even to British speakers, because of the use of “r” to mark long vowels and linking (badger and hen: /bædʒərændhεn/).

The more directly-phonetic spellings would still be permitted for these. Words that vary substantially across accents (rather than just the vowel sounds shifting slightly) would have several permissible spellings, such as ask: “ask” (N. British) vs “aask” (S. British; in many worldwide accents, it would be spelt “aaks”). One could prefer a foreign spelling and learn to pronounce it natively – I might write “ask” for instance.

Phenomena such as syllabic consonants would introduce alternative spellings as well, such as syllabic l/n (mission: “miſxn” vs “miſn”; bottle: “botxl” cs “botl”), and weak-vowel ambiguity (ə vs ɪ) would do the same, whereas tightly-scoped regional allophonic variations would be subsumed by the relevant letter (e.g. the t in bottle can be pronounced [t] (standard) or [ʔ] (Bri’ish) or [ɾ] (baarrlll), but is always spelt “t”).

Weak vowels

Kids will always spell forget “ferget”, so my spelling system would help them out – it’s “fxget” not “foget”. This creates situations like photo (“fowtow”) / photograph (“fowtxgraf”) / photographer (“fxtogrxfr”) depending on which vowel is typically reduced. Thus, alternative permissible spellings that would make the etymology clearer are “fowtŏgraf” and “fŏtogrăfr”, with the understanding that the breve sign ˘ indicates a weak vowel, so pronounced the same as “x” (or potentially “i” in some cases I couldn’t tell you about). But this is only for education really. Pronouncing these words without any weakening still sounds vaguely English (second language–ish).

Weak forms

In most cases, writing weak forms strongly helps regularise the orthography, so “much to do” would be written “mʌtſ tuw duw” rather than “mʌtſ tx duw”. The only exception that comes to mind is that “the” should be treated more like “a”/”an”, with variant spellings, so:

- a/an: x/ey/an

- the: ðx/ðiy

History

My top priority was undoing the Great Vowel Shift, so having corresponding short and long vowels once again sound similar to each other and more in line with other European languages. Beyond that, I picked a few letters from old and middle english (þ, ð, ſ) in order to return a bit of the language’s Nordic roots. Looking at the sample text, it looks quite Nordic to me, and used to even more so when I was using “ø” instead of “x” (you can do a quick replace-all to see this).

One thing that’s a bit radical with respect to Germanic language tradition is ditching the double consonants as markers for short vowels. Both this and vowel reduction are, as far as I can tell, very irregular, so I broke from the traditions and gave ‘em the boot.

Spelling Reform: Alternative

Another way to fix English spelling is to regularise its goofy rules. So say we try to obey the “double consonant (or single word-final consonant) → short preceding vowel” rule, same as in Dutch, and we lay out a set of standard spellings for the long vowels:

| type | short | spelt | long (→r) | spelt | long (→j) | spelt | long (→w) | spelt |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | æ | a | ɑː | aa/ar | ɑj | i | æw | ou |

| e | ɛ | e | ɛə | are | ɛj | a | ||

| i | ɪ | i | ɪə | ere | ɪj | e | ||

| o | ɔ | o | oː | au/or | oj | oi | əw | o |

| u | ɵ | u | ɵə | ure | ʉw | u/oo | ||

| ʌ | ʌ | ʌ | ||||||

| ə | ə | - | əː | er/ir/ur |

The difference between u and oo would be the former palatalises the previous consonant and the latter doesn’t, as before.

So vowel reduction works as before, and long vowels followed by “r” are still kinda reduced to the əː phoneme (which does actually split into er/ir/ur in Scottish English, as well as centuries ago everywhere else), becoming “truly” long when followed by magic “e” as usual. There are other archaic rules we might maintain, especially for word-final vowels:

- “a” is always short and reduced to ə (“sofa”), so “ay” is used for long a (“stray”)

- “e” is silent (indicates prior long closed vowel), so “ee” is used for long e (“the”, “babe”, “babee”, “silentlee”) unless monosyllabic word

- “i” is always spelt “y” (“cry”, “hy”, “y”) and used for long i

- “o” is always spelt “o” and used for long o (“so”, “tho”, “glo”)

- “u” is spelt “ue” and used for long u with palatised consonant

- “oo” is always spelt “oo”, used for long oo

With all this shite, we end up with:

Former Wimbldon champyon Boris Becker’s bancrʌptcee has offissyallee ended, after a UK jʌgge found he had dʌn “aul ðat he resonnablee cud doo” too fuffil hiz financyal obliggasyons. Ðe German tennis player woz declared bancrʌpt in June 2017, owing creddittors aulmóste £50m. Ðe Hy Cort woz told he stil oed abbout £42m – bʌt lauyers for Becker sed ðe 56-yere-ólde had reechd a settlment agrement wið ðe trʌstees appointed too oversee hiz finances.

Yeah, no lmao. “oo” would need to be repurposed for forcing long “o” (i used “ó” as a crutch) but tbh there’s no saving this cos it just looks like arse.

offissyallee